Meditation is a fragile word. Use carefully.

The frenzy of half-baked meditation ideas flooding the media has sidelined an important concept that many of us have been searching for our entire lives.

Sometimes you have to start a little before the beginning.

You’ve heard the phrase “coming to terms.” We spend a little extra time in the early minutes of a conversation to make sure we agree on what important words mean.

Meditators —new and old — have to do this. If we don’t the disagreements and assumptions get troublesome. Or comical. So we have to do it, and the more we do, the better we get at it.

And first things first, we have to wrestle the slippery term “meditation” into something consistent. Because everyone who uses it seems to think it means one thing — often their thing — but year by year it has weakened to a point where doesn’t really mean anything.

So, let’s consider what it is trying to mean. We’ll see that an old word has been given new meanings. Maybe too many of them

Hey! Subscribe for free to read all the articles in this series.

“Meditation” is an attempted translation. That’s all.

We have to start with an agreement.

Do we agree that “meditation” is an English word? Do we agree that it usually points to something outside the realm of English-speaking culture?

Please say “yes.”

As one who lives and breathes in the world of meditation teachers and students, I’ll put out there that the common usage these days points to the inner practices of the mind developed simultaneously and cooperatively by Buddhist and Hindu traditions 3000 years ago, long before the English language existed. Not everyone knows the details, the “3000 years ago” part, or even the “Buddhist and Hindu traditions” part. But somehow, they get that anyway.

When people say meditation, and they don’t mean this, they often have to clarify that they mean something else. Because in common usage, meditation means that quiet thing people do on the floor, or maybe these days, on a chair.

So right away we know that meditation is a translation of some other culture’s word. And translations are usually a best attempt to convey meaning, not always exact — translation is an art, not a science.

Some words are almost impossible to translate into a single word. Often you need a string of words, or a paragraph, to convey what comfortably fits into a single word in the original language. Here are some examples:

saudade

The Portuguese word saudade means a longing or nostalgia for someone or something that is no longer there, and it also indicates an uncomfortable knowledge that the person or thing will not return. No single English word conveys the full meaning of saudade. This is sometimes translated as “nostalgia” but doing so leaves out the nuance of the original meaning.

And most English speakers don’t use or recognize the word saudade, and they also don’t carry the meaning of it, because only the word can allow them to do that.

hygge

The Danish word hygge is usually translated as coziness. But hygge means a lot more than coziness, it carries a sense of comfort, togetherness, and well-being that is a defining part of Scandinavian culture. It is not mere “coziness” because it includes an emotional state as well as a physical state, and beyond both of these, it carries a sense of finding joy in the simple, everyday things in life, enjoying good things with good people.

There is no English word for this, and nothing in English wraps this meaning into a culturally shared concept. English speakers don’t experience hygge, at least until they have the word in them.

The important point is that without the word, the meaning isn’t necessarily present. Sometimes it is, though: snow and the French neige mean more or less the same thing. English don’t need the word neige, because they have the word snow.

But as with saudade and hygge, other words are doorways out of our cultural vocabulary and into another.

The word meditation almost tries to prevent that door-opening from taking place.

Choosing the right word

Meditation as it is used in Buddhist and Hindu contexts has layers of meaning that no English word can mean. And not just that, the ideas contained in the original are ideas that don’t exist natively for English speakers unless they venture outside of English language ideas.

When we try to translate meditation we run into the obstacles and biases of the English language, things we don’t usually notice because we are so used to them.

Until the 1990s almost everything we heard about meditation was framed in Western religious frameworks. Meditation was compared to a type of prayer or communion with the divine practiced in the “religions” of India. (Sounds like Victorian thinking, makes me nauseous.)

In the 1990s, a second framework became popular: that of psychotherapy and the wellness movement. These may appeal to us because they are familiar, but that doesn’t mean they accurately communicate what meditation is. (My take: they don’t.)

Through our translations, we may be missing out on something important. In order to find, out, we can bypass the Western frameworks of religion and psychotherapy, and look into the words and practices as they exist in their own world.

We can look at the Sanskrit, Pali, and Tibetan languages, which are the source for most of the information on what we call meditation practice. And by source, I don’t mean “way back a long time ago”. These terms are still in active use all over the world, they mean what they mean in a fresh, everyday way.

Meditators I know use Sanskrit, Pali, and Tibetan terminology fluently, easily, happily. Not that they actually speak these languages, but the meditation vocabulary is firmly in their grasp. Without, it, talking about meditation is reduced to silly childlike ideas like “monkey mind” and “feeling centered.”

Meditation isn’t a casual practice for casual people, it’s a deep practice for open minded, energetic discoverers who aren’t afraid of adding a few more words to their vocabulary.

“Meditation” is a lazy translation that encourages laziness

As mentioned, “meditation” is a single English word that tries to do the work of many technical, specialized words from the cultures that developed meditation.

Some of the important Sanskrit words used for this practice are dhyana, samadhi, smriti,and vipashyana. (Conventional translations for these are, in order, concentration, meditative absorption, mindfulness, and direct insight.) These are not synonyms, they are deep, nuanced words that have layers of meaning appropriate to the stages of the meditation journey, they hold shades of meaning important to the overall picture. But all of them are frequently referred to as “meditation.”

Of course, if all you’re doing is trying to “tame your monkey mind” or be more “centered” you don’t need these words. But for people interested in the actual depth of the meditative experience, you can’t do without them.

In fact, there are cause-effect relationships between these words: dhyana results in samadhi. Smriti can mature into vipashyana. The single word “meditation” doesn’t even hint that such a dynamic exists. It’s a shallow word that hides meaning. In my book, that makes it a bad, or at least a profoundly lazy translation.

In Sanskrit, there is no single term that tries to unify all these words. But in English, we have “meditation” and that really is just about all we have. Are we lucky? (No, we’re lazy.)

Imagine if we only had a single word for all the creatures that live in the forests and jungles and savannas. What if they were all simply called “beasts” with no further detail? Your parents took you to the zoo, and you saw “beasts”. The tiger was just “beast.” The elephant was just “beast.” What kind of conversation could follow that trip?

Simplification keeps us small

The way this has played out in the west is that many new students think the practices they learn at first are the whole thing, they are “meditation.” When they learn that somebody else practices “meditation,” they assume that person is doing the same thing they are.

People think the Dalai Lama sits with his hands in a yoga posture and follows his breath, because that’s what they think meditation is, because that’s what they were told.

When you learn “meditation” properly, what you do in the first year is probably different from what you do after that. And as you advance, the things you do as “meditation” are far more profound and impactful. Your practice changes. The Dalai Lama is not doing what you do. He is doing something deeper. Much deeper.

In more knowledgable circles, people ask one another “what practice are you doing these days?”. That reflects a knowledge that the term meditation is too general to be useful.

True mountaineers don’t land in Nepal and ask where to find the “big mountain”. They at least know the names of the peaks, the cities, the towns, and learn a few Sherpa words. They care, they learn, they become experts.

Meditators who don’t learn the language of meditation are not meditators. You can’t talk the language of direct experience with them because they are too lazy to learn anything and thus, to know anything. They get nowhere over many years. Meditation doesn’t play nice with laziness.

This English word is under a lot of pressure

I like history when it comes to language, to see how words and associated ideas develop over time. It began when I was an undergraduate studying Greek to (slowly) read Plato. I was a poor student, but even I raised my brows at how much words depart from ancient roots.

Look at the word philosophy. Greek word first, then the modern equivalent.

Philosophia: the love of wisdom (from my education in Classics)

Philosophy: the study of the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality, and existence, especially when considered as an academic discipline. (From my laptop’s built in dictionary.)

I’ll just say, yikes. The first inspires me, moves me to learn and explore. The second sounds like a bunch of pretentious people in a department competing for status in a dead discipline.

Meditation, the way people like me know it, is a form of the first. It is the love of wisdom, it is the proposal to wisdom, the beckoning, the heartfelt seeking. It’s what you do after you’ve pulled everything you could out of reading. Once you get to meditation, you mean business.

Anyway.

Meditation as an English word once meant its own thing. It didn’t work for someone else like it does now. It had its own history and it’s own usage, but that history has been overshadowed by our demand that it hold these ancient Sanskrit meanings, and hold them all at once.

And then we put new, seemingly random New Age meanings into the expectation, and in the 1990s, as it started to strain under too many meanings, we began to offload some of the excess into the new darling of too many meanings, mindfulness. We’ll get to that in a later post.

First let’s be rare people who actually understand what the original English word meant.

Ye olde meditation

Once upon a time, some time around the year 1250, the Latin term meditari meant “to reflect, to contemplate, to think over.” My dictionary tells me this, but I can find no examples of it anywhere, at least not anything that looked convincing. That’s as early as we can go with a root of this word. (if you are a latin scholar and can help, please leave a comment.)

Somehow, and I don’t think we know how, it made its first appearance in Middle English as “meditation” within a rule-book for nuns (the Ancrene Wisse, or Anchoresses' Guide). These would not be Buddhist nuns, of course, but nuns of whichever Christian tradition used the Anchoresses’ Guide, thought to be either Augustinian or Dominican.

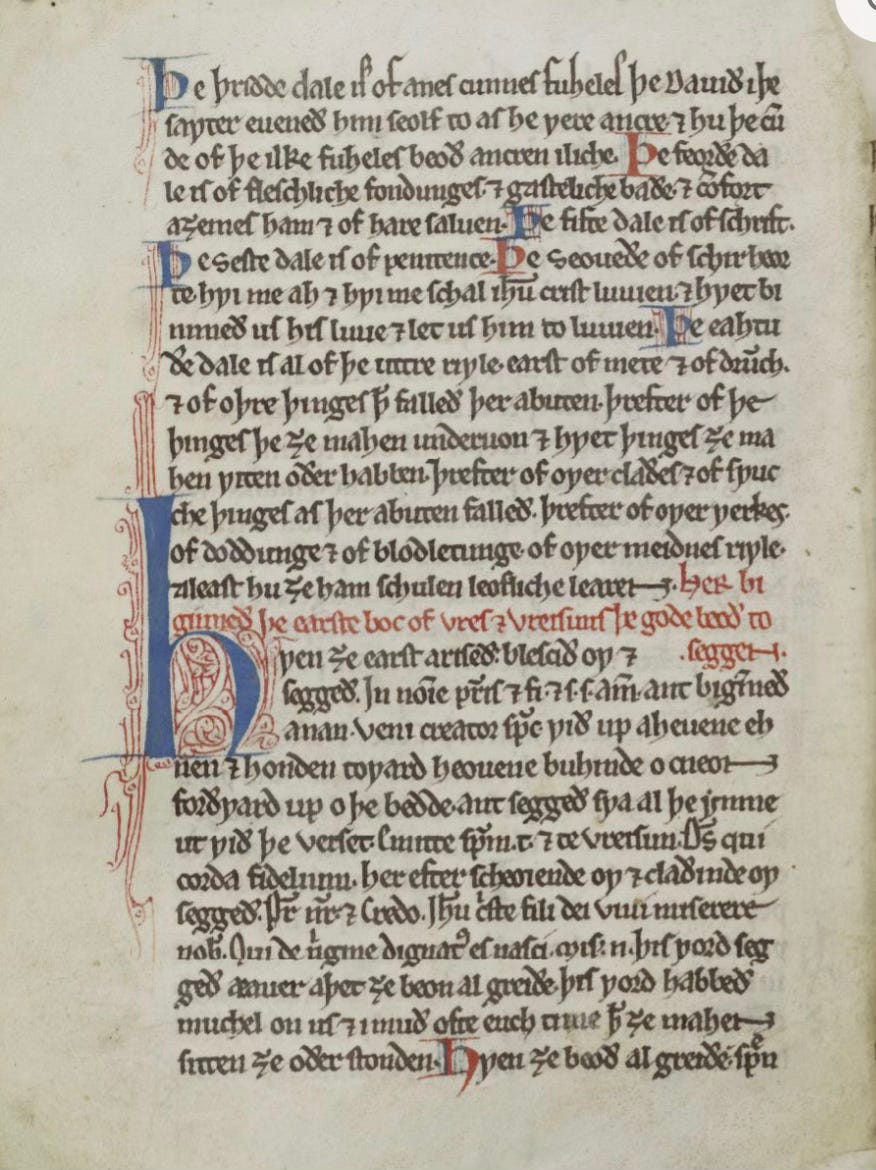

Here it is for your reading pleasure, the nearly 800-year old first known use of the term meditation in English (albeit translated from Middle English):

Whatever other devotions you use in private, as Pater nosters, Hail Marys, psalms, and prayers, I am quite satisfied that every one should say that which her heart most inclines her to, a verse of her psalter, reading of English or French, holy meditations. (Translated by: Robert Hasenfratz)

That’s a significant little bit of literary history right there. Here’s a page from it:

Source: https://purl.stanford.edu/zh635rv2202. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 402: Ancrene Wisse

(Honestly, I couldn’t get through it. I just gravitate toward more modern sounding stuff. Shallow, maybe, but that’s how I am.)

Now, this instruction to the nuns most definitely is not what we mean by “meditation.” The nuns of 1224 were not engaging in the practice of sitting cross-legged and following the breath, or doing any of the other stuff “meditators” do.

Still, it is a powerful indication that “meditation” had an exalted purpose in its English context. That qualifies it, somewhat, to represent the exalted practices of the ancient world. But to put 3000 years of practices into one single English world makes nuance unlikely.

So if we were trying to preserve access to these valuable practices, we didn’t work very hard. We have one word, not several, and it partly reveals, and partly obscures what it tries to represent.

Yet that isn’t even the worst of it.

Here comes the Instagram crowd

Nowadays (thanks, Instagram) the term meditation is used for things which have no “exalted” purpose at all. Just look at Tiktok, Instagram, Facebook, or Youtube. There, you will find meditation to help you…

“Magnetize” money through harnessing a universal money vibration

rapidly improve your health and wellness (and maybe younger skin)

increase your focus to optimize job performance

“manifest” the life you were born to live

And on. And on. Not exalted, not the stuff of nuns, and not the stuff of Buddhists.

When you see what people are willing to call meditation, you’ll see how unrelated the meaning can be.

Freedom to confuse

It’s a luxury of the modern world that we use language almost however we want. Freedom of speech gives us freedom to use our discretion to either preserve or degrade the access points our language gives us to rare and valuable ideas. Right now, meditation is losing its meaning, and this can remove access to something we don’t have another way into.

coming to terms anyway: a definition

So how do we solve that problem? By coming to terms.

We would only take the time to come to terms if we thought the result was worth the work. In this case, we should push forward even if we don’t yet understand why. The fact that meditation exists at all should amaze us. The fact that it didn’t develop in the modern Western nations, or come about through science should encourage us. It came about long before the “West” existed. And long before science was a thing. And yet, it unfolded and hasn’t needed tweaking in all that time. It is a true human discovery, pre-science, and pre-modernity. And nothing can touch it!

Meditation, once you see what it is, becomes really, really valuable. You’ll have long moments of jawdropped amazement when you start to see what is possible to you through taking up an activity that develops you from the inside out.

So let’s come to terms with the word “meditation”.

Meditation is the inner practice of engaging mind and awareness to remove fear and confusion.

That is the basic meaning of meditation (at least here, and most places that teach classical styles).

So now that we have a meaning, we should also be clear about what is not included in that meaning.

Meditation does not mean:

A way of optimizing your life for better performance.

A way of tricking the universe into giving you what you want.

A practice aimed toward a really good feeling.*

A relaxation or concentration exercise for its own sake.*

*It’s possible to press classical instructions to serve these goals, but good luck finding a genuine tradition willing to help you do so. And it’s far too involved (time consuming) to try this on your own. You need instruction.

These uses of the term meditation are all restricted to trends dating no further back than the 20th century. They have little (probably zero) track record, they’re just fads. Or to be blunt, they’re ads. Ads for products that will only consume your time.

Enjoying this? There’s lots more for free when you subscribe!

This article is part of the Meditation 101: Six Ideas to Clarify Your Practice

You can read the rest of the series by following these links:

something real for a change

The classical practice of meditation has the most substantive track record for any undertaking with a traceable lineage. It is taught today in almost identical manner to the way it was 2500 years ago. It is tried and true, reliable, and peer-reviewed.

We shouldn’t confuse this with less serious, more fantastical practices that show up on social media and use similar sounding language. They are not the same. They aren’t even similar.

The problem arises when a 2500-year-old tradition is used to sell things that have no serious purpose. It’s a misrepresentation that obscures the real value of having such a deep tradition in our world and all it takes to maintain it for new generations.

Having images of traditional meditators in your advertisements when all you are trying to do is get people to buy your recordings of “space vibrations for love & money” is deceptive. If we want to cheapen things in our attempts to market our wares, I guess that is legal. That is, it is legal for people of no character to do things like that.

But to cheapen something that took 2500 years to develop seems reckless. Meditation does not exist to make people rich, it exists to make people free. Like the Redwoods, like the oceans, it is something worth protecting.

And true meditation is not deceptive, it is the opposite of deception: it is reality revealing.

Next in our journey, we’ll look into the part of us that meditates: the mind. This is the beginning of the reality-expanding power of good careful language.

Take care my friend,

Jeffrey