Mindfulness: it's been a rough 30 years

Mindfulness is an important component of a bigger system of mental cultivation. It isn't much of anything on its own, which is why it has become a meditative clown farm.

Today we open the biggest can of worms in modern meditation: mindfulness.

mindfulness seems to mean anything you want

This one term has lost its original ground, which is to say, it’s being used for far too many things, while not really meaning most of those things. It does mean some things, but it doesn’t mean everything marketers are trying to make it mean.

even meditators don’t agree

Remember how we talked about the word “meditation” going through a process of meaning first one thing and then another thing, and now just about everything? Mindfulness is in the same situation.

It is so overused in meditation circles that practitioners of one tradition may mean something almost unrecognizable to what practitioners from other traditions mean.

For example, though both use the word in their teachings, the popular Vipassana community doesn’t mean the same thing that the ancient Mahamudra traditions do. You wouldn’t immediately identify the similarity between the two. Vipassana uses mindfulness to mean present-moment centered, nonjudgemental awareness of what is happening in the body and mind.

Mahamudra uses mindfulness most often to refer to the fundamental self-remembering of the awakened state, or for beginners, the recognition of the awakened state that returns one to awareness after distraction.

These aren’t the same, and both of them refer to aspects of our inner beings which meditators from any traditions can understand. So even if they aren’t shared definitions, they would be points of shared understanding. What I’m trying to say here is that they are different but not points of disagreement, per se. They are divergences of emphasis among extremely sophisticated meditation traditions that all definitely know what they are doing.

But then we have modern definitions that just turn out to be bunk: no traditional Indian texts share the psychologist-approved modern meanings taught in corporations to reduce burnout and level up productivity.

I have heard so many of these that I can’t remember them. They aren’t memorable, because they aren’t useful for mediation. You don’t need a staircase to walk across a floor you are already standing on, and you don’t need trendy notions of mindfulness to tell you what you already know (relax, pay attention to your life).

and then there’s the marketers

But it’s not just within meditation, now there are fad movements in every sellable niche from business to sex to weight loss, all operating behind the word mindfulness.

When the grocery checkout counter has a magazine dedicated to something, it’s probably not for you. The books at the library on the same topic — those are for you.

You don’t know what someone means when they say this word anymore. Their “mindfulness” — what is it? Is it meditation? Probably not. Maybe it’s self-help, or their life-hack toward minimalism, or decluttering, or making money in a more “sustainable” way.

All this tries to live inside one word. We’ve been here before.

Too much of a good thing: the tipping point cycle

Remember Taoism? If you walked through bookstores in the 1980s, you saw the same thing happening to the word Tao. I saw it go through three phases: pre-tipping point of obscurity, tipping point of great expansion, and post tipping point/meaningless sellout.

First, tao meant the central conception of the Chinese tradition, Taoism. Not many people were aware of it, but those who were had translations of a few seminal texts to study. It was pre-fad, pre-tipping point. Obscure things of interest only to dedicated meditators, like Yogachara-Madhyamaka, or Dzogchen, are still at the pre-tipping point in 2025.

Then, for some reason, it caught on and became a popular thing for translators to expand: Tao te Ching, Chuang Tzu, Sun Tzu (Art of War, kind of Taoist -adjacent reading, very popular) and of course the many translations of Thomas Cleary. This was the full-fad, the tipping point stage. Mahamudra is at this point right now.

Then it meant “the word you put on a book jacket to sell your scheme.” This is the post-tipping point, where it became more of a vibe. In current days, “tantra” has been here for a long time, becoming meaningless and empty, almost automatically associated with sex (inaccurately so, as the tens of thousands of monastic tantric practitioners demonstrate). And now Zen has reached this moment, sad to say. (Not actual Zen practice, just the notion of Zen, as in, “find your zen.”)

By the 1990s tao had as much to do with finding your edge in Wall Street as it did anything deep. Then, as all things eventually must, it was pulled into books on sex. The tao of sex. I am not even going to check amazon right now to see if that is a published title. It must be.

Mindfulness is full-blown tipping point sellout stuff now. I can only imagine that teachers from traditions which rely on the term mindfulness in its legitimate context are laying awake at night wondering how to navigate the nightmare. I feel for them. If that ever happens to my traditions (mahamudra and dzogchen) I’ll leave society.

Ok, enough of that.

Despite all this, it’s an important word

Keeping to our mission, let’s talk about mindfulness only in the context of meditation, not in selling magazines to busy, stressed out people.

And also in keeping to our mission, let’s reiterate our terms. First, our definition of meditation:

Meditation is a method of working with mind and awareness to free ourself from fear and confusion.

Mindfulness has at least two very different definitions in meditation instruction. Let’s take a look, because they are both very helpful. They are two very good meanings that make a big difference in the practice of freeing ourselves from fear and confusion.

First things first: where’s the word come from?

India.

The word mindfulness goes all the way back to ancient Indian literature and beyond. There you find two vital words each translated as “mindfulness.” Smrti, and sati. That first word looks hard to pronounce. But it’s actually easy: “smree-tee”. Said quickly, like “T.V.” Go ahead: give it a try.

Did you do it? If so, you spoke one of the most impactful words in human spirituality. Smrti has been in continuous use for 4000 years. Think about that. It’s been used in the same way all that time. And we just used it here, in 2024. It means right now what it meant all the way back then.

4000 years of continuous use. That’s when you know a word must mean something important.

The other word, sati, is still very old, but came later. It means the same thing, and lots of meditators use it instead of smrti.

These two words are from slightly different dialects of ancient India: Sanskrit (smrti) and Pali (sati). Both are major resources for meditative literature. That’s it for today’s history and linguistic lesson. Let’s dive into the meaning.

mindfulness in translation

There are no popular contenders to the word mindfulness, it’s what nearly every translator uses, so we’ll use it too.

In a refreshing coincidence of harmony, I have no quarrel with it, because it really does a great job at meaning what all those ancient words mean. On top of that, it’s a good old English word going back to the 1500s (“myndfulness”). Sometimes things work out!

Remember of course, Indian meditators didn’t use the term mindfulness, because it didn’t exist yet, because English didn’t exist yet.

And in English, myndfulness/mindfulness wasn’t pressed into meaning “meditation” until 100 years ago, after which it lost much of its original identity. It had 400 years to be a good English word before it was taken over by the need to translate Sanskrit.

It still lives in the shelter of the English underground transit, where you hear “mind the gap” at regular intervals over the intercom. It means, don’t fall onto the rails, which isn’t the same intention in mediation. But it achieves this message by using the term “mind” as a verb. Mind the gap. Don’t be mindless and fall onto the rails.

That preserves some of the original meaning, and also bridges into the ancient Indian meaning too. That’s part of what makes it such a good translation1.

In its ancient Indian meaning, mindfulness (smrti/sati) means: memory, recollection, retention of information, collectedness.

But if only it were that simple. Actually, this is a point where high level “controversy” comes in. Nothing discouraging, nothing divisive, it’s just that there is a solid disagreement that shapes modern meditation traditions. And it will make us smarter just hearing about it.

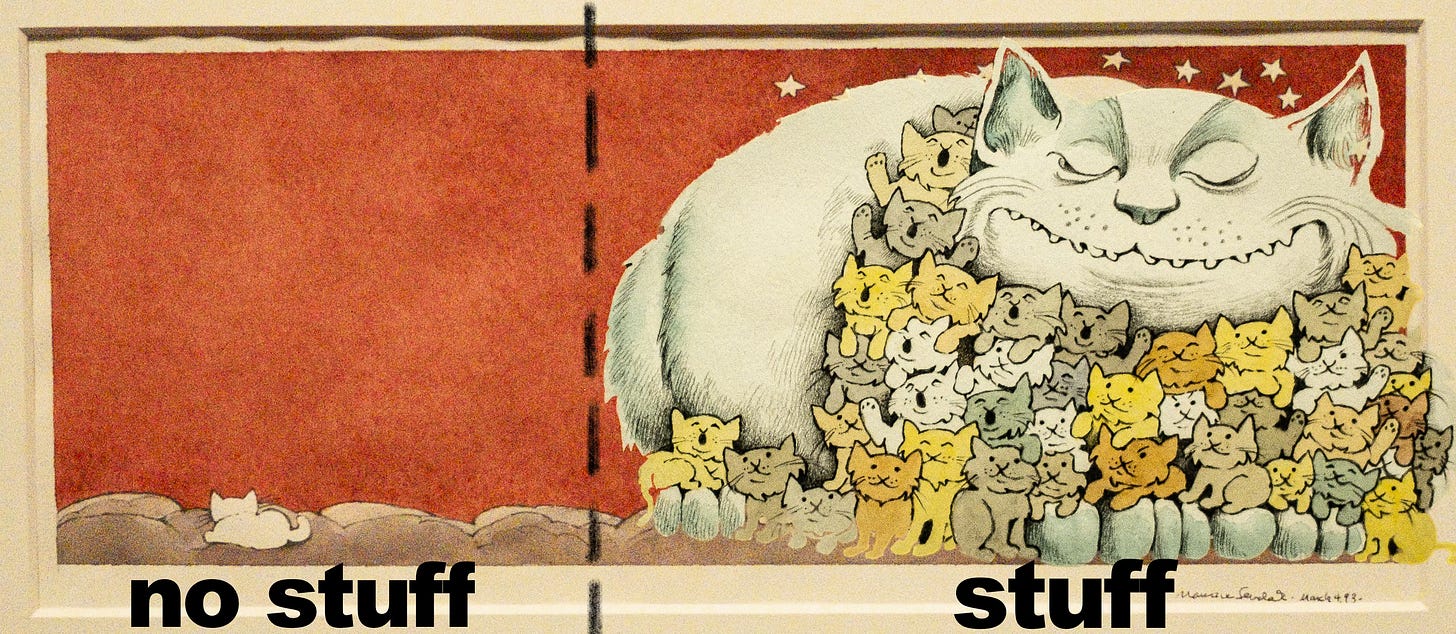

Stuff or no stuff?

Historically, mindfulness (smrti/sati) implied keeping in mind the essential teachings of the path: the understanding of impermanence, nonself, and so forth. Mindfulness meant, at least in part, to maintain a relationship to this understanding.

And that means mindfulness keeps information in mind. It retains stuff. It has to, right? How else is it going to be “mindful” of something it learned? I want my doctor to be mindful of anatomy when they poke me. They need to remember that my arm and my eyeball are two different things. (Modern exponents of this view would be Achaan Cha, and Bhikku Bodi). To me it appears to be what the historical Buddha taught, and it is what I learned in grad school when we looked at those old sources.

But things changed: a modern turn, sometime in the mid 1900s in South Asian practice (Mahasai Sayadaw and Nyanaponika Thera, etc.) removed the stuff altogether, and argued that mindfulness is a type of bare attention on the present moment. In this use, there is no stuff, only the present moment into and out of which stuff comes and goes.

These two meanings are different, yet genuine traditions that pursue the same goal find ways to operate with the differences of meaning in this one word. I like both of these traditions, and I like the teachers from each side of the “disagreement.”

I lean toward the first definition of mindfulness, but then again, my meditation training didn’t emphasize mindfulness, it emphasized awareness (which we’ll talk about in another post). In awareness, there is no retention of knowledge, it is more like the second meaning of mindfulness: bare experience.

So to me, mindfulness includes an understanding of the nature of the relative world: impermanent, encouraging fixation and grasping, and essentially empty. In my tradition, and in the way I teach, mindfulness is a knowledgeable state of mind that is free from clinging and fixation.

Just to be clear: I am cool with both definitions. These are great traditions either way you go.

two camps, one campfire?

So now we have two competing meanings.

The original, basic word meant “memory” and was used by the Buddha to teach meditation. And the Buddha seems to have implied that mindfulness would include knowing things, keeping a wise outlook, not forgetting essential information. Just like a surgeon has some level of anatomy and technique in mind during a procedure, a meditator also is loaded up with training that is kept in mind even during meditation.

And now we have this modern interpretation, popular in recent meditation communities, where mindfulness signifies bare attention to the present moment.

Both share some things: In meditation, they often mean being collected rather than distracted, or present to what is actually here. Whether or not that collectedness includes information one tries to maintain, such as a meditation instruction or a teaching on reality, is up for debate.

But nobody is going to win that debate, the traditions are dug in where they stand.

This isn’t a big deal for us, it just means we have to recognize which meaning we are depending on in the type of meditation we’ve learned.

Example: what I teach

I teach Finding Ground Meditation, which is my presentation of the Mahamudra system of India and Tibet. My teachers, and I along with them, use mindfulness in a specific way that simply means being attentive to one’s current state of being, and recognizing its characteristic of impermanence, emptiness, and the painful result of trying to cling to it or solidify it into something lasting.

This simple way of talking about mindfulness works because we have a rich way of talking about other parts of meditation that some traditions don’t have. In other words, we have a rich vocabulary that doesn’t need to pack everything into one word. Mindfulness is an important part, but a somewhat smaller part, of our instructions. And that is notably different.

Words can define traditions

For some traditions, the practice is “mindfulness.” That’s it, that’s the whole thing. As in, “what do you practice” “I practice mindfulness.”

For other traditions, especially those with more ancient roots, mindfulness can mean the development of sustained attention in meditation, and it can also mean luminous awareness of the sensory and mental world.

Not only that, it can be dynamic. The meaning attributed to it within a tradition may shift as practice becomes more and more powerful and advanced instructions replace preliminary instructions. The “mindfulness” you begin with is transformed into a more potent, more effortless mindfulness later on. As you grow, so do the elements of your vocabulary.

Finding Ground Meditation follows the approach of a classical system. Here, “mindfulness” is an important part of the mind, and you need it to practice meditation. You begin meditation by developing mindfulness, and then you graduate to a deeper type of mindfulness,— an effortless style of maintaining awareness, which begins to stabilize itself from within itself. That’s deep stuff right there!

Putting it all together

In the practice of meditation, one learns to strengthen mindfulness so that they can disentangle themselves from patterns of fear and confusion that have been born from lack of mindfulness.

At first, meditation reverses the damage done through weakened mindfulness. This accomplishes a level of healing, making us fit for a further journey. When the healing is well underway, some traditions of meditation transition the emphasis from mindfulness to awareness. Finding Ground, along with Mahamudra and other awareness-based traditions, does this.

Our foray into mind and mindfulness paves the way to talk about the most important idea so far: awareness.

Mind is the part of us that knows the things in the world, awareness is the part of us that knows ourself.

Awareness is a very subtle quality of our being, and training it through meditation accomplishes great things. Awareness is the domain of real transformation, and that’s what we’ll talk about next.

Jeffrey

This article is part of the Meditation 101: Six Ideas to Clarify Your Practice

You can read the rest of the series by following these links:

There’s another fun level to the phrase “mind the gap” that English meditators smile about. The gap (Tibetan: hedewa), in buddhist practice, refers to a point where one thought ends and the next thought hasn’t yet appeared. It is a moment of no thoughts, a break in the storm. It lasts a second, and then the next thought appears and thinking resumes. Most of us never actually recognize that this happens, but it does, constantly.

This moment is referred to as the gap, and it is something meditators train themselves to recognize and relax within, which causes it to expand. Mind the gap sounds like good buddhist encouragement, and Londoners hear it dozens of times a day when they commute on the Tube. No wonder they are so civilized.